Local Area Network

Local Area NetworkThe Local Area Network

Even if you don't plan on letting the big, bad Internet anywhere near your PCs, a home network still has many uses. Many of the basics of setting up the two types of networks are the same. In fact, even if you are planning on sharing a broadband connection, the place to start is right here. Don't skip to the next section without getting the items in here working first. The best approach I've found for creating a broadband connection sharing network is to start with a working LAN and then add the Internet connection.

A typical Internet Service Provider (ISP) will supply the connection to the Internet through some device that converts their wiring coming into your home (be it cable, copper telephone wires for DSL, fiber optics cable or something else) into a standard network drop. They often also include - either separately or as part of the same device - a router & firewall with one or more ports for your LAN to connect to. That's generally where their work and responsiblity stops. If you have more than one computer to connect to their equipment, that part is left as an exercise for you. That's the viewpoint from which these pages were written, and if you're trying to create a working home network using them, your journey will be more blissful if you proceed in the same manner.

Wired Network

Wired NetworkWired Networking Equipment

This was probably the part of the home network that you suspected you needed. The hardware. The stuff that connects it all together. To create a home network you need a couple of things. If you're planning on installing a traditional wired network, you need 1.) a port (jack, connector) in each PC that you want to connect (or in every other device like an Xbox or DSL router), 2.) an Ethernet cable to connect each device to the network, and 3.) a router or switch (or combination router/switch) that lets you connect all the cables together. If you're thinking of installing a wireless network either instead of or in addition to a wired network you will want to make sure to read the section on.

This section discusses in detail the basic equipment needed for a wired network for both the LAN and Broadband Sharing networks, and outlines the differences where appropriate. If you are planning to have a wireless network, you will have somewhat different equipment needs. You'll still have to deal with a couple Ethernet ports and at least one cable, most likely, but much of what in this section won't be as applicable. You should skim the beginning of this section and then proceed on to the section on Wireless Networking Equipment. If your network is going to have some wired devices and some wireless devices, you get the fun of getting both to work, but start with the wired portion of your network first.

Wired Ethernet Adapter

Whether it's a card that you install yourself, it came built in on your desktop or laptop, or it's some other type of Ethernet adapter, you need a physical Ethernet port for every device you plan to connect to your home network. These are analogous to the jack on the back of a telephone. Originally, a Network Interface Card or NIC (pronounced "nick") was a hardware card that was purchased separately and installed inside the computer to provide a physical Ethernet port outside of the case. However, it's now very common for new desktops and virtually all new laptops to come with an Ethernet port built in.

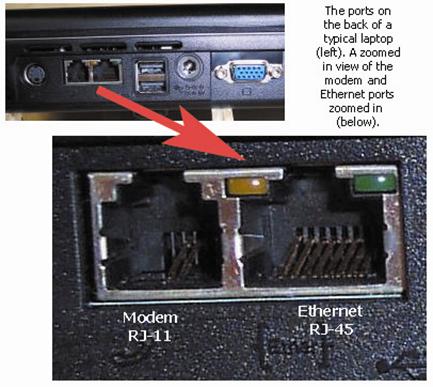

If you're hooking up fairly new equipment on your home network, you should first determine which, if any, devices are going to need to have an Ethernet NIC (a.k.a. Ethernet adapter) added. Look at the ports on the back of your desktop, laptop, or gaming console. The Ethernet port looks like a RJ-11 modem jack, but it's physically wider and has eight copper/gold connections inside instead of the two or four that a modem jack has. On newer desktops, a built-in Ethernet port is usually found near the USB or keyboard ports. The following table lists several different kinds of Ethernet adapters along with their features and uses.

| If your desktop computer doesn't have an Ethernet adapter already, you can install a NIC (like the one shown to the right), the Linksys LNE100TX. (Unless the computer in question is older, it's very likely it has a built in Ethernet port. Check along the back for an RJ-45 jack similar to the one in the picture.) |

Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| For those of you who have computers without built-in Ethernet ports (especially laptops) and don't feel up to mucking around inside your computer to add one, there are also USB to Ethernet adapters like this one shown at the right. The USB end of this adapter includes a USB cable that plugs into any available USB (2.0) port on your desktop or laptop computer. The other end has of the adapter has a standard Ethernet port. (It's very unusual for any late model laptop to not have a built in Ethernet port. A number of netbooks do not have such a port, so this type of adapter is useful for those.) |

Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| Another alternative for laptops without built-in Ethernet ports is a PCMCIA Ethernet card like the one shown to the right can be also used. This card slides into a PCMCIA slot on the side of your laptop. If this is an option on your laptop, this adapter is preferred as it is faster than a USB connection. Unfortunately, PCMCIA (and Cardbus) slots have fallen out of favor as of late, so such ports are becoming rare. That said, laptops without the PCMCIA/Cardbus slot most often do have an Ethernet adapter port built in. |

Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

Some terms you will often hear mentioned in regard to telephone and Ethernet ports (jacks) are RJ-11 and RJ-45, respectively. RJ-11 is the 4-wire (or 2-wire) jack used with telephone (modem) connections and RJ-45 is the 8-wire jack/cable used with Ethernet connections.

Once you have installed the Ethernet adapter and loaded any drivers to support it (if necessary), it's a good idea to check to make sure that the operating system has recognized the adapter, and all appears to be in working order. Do that by performing Testing the Ethernet Adapter section.

Cables

If the Ethernet ports are the equivalent of the phone jacks on a telephone, the cables are analogous to the telephone wires that connect the telephone to the wall jack. Like telephone cables, they come in a variety of lengths and colors. Also, like telephone cords, Ethernet cables are almost always male-to-male plugs in terms of the connectors on the end like the picture to the left. For this discussion, we are going to assume that you are using pre-made cables for your home network (or that your home network was professionally wired and the only cables you need to be concerned with are those from the wall jacks to the devices attached to the network). You will need one cable running from each computers, game console, printer, etc. that you plan to connect together. Even if your network is going to be "totally wireless," you'll may still need a cable or two for your Internet connection (if you have one)

Like telephone cords, if you wish to have cables that are exactly the right length, you can make your own. Even if you are planning on wiring your home as part of installing a home network, it's probably best to start with pre-made cables. That tends to eliminate one variable in the event you have problems getting your network up and running. (You can start with pre-made cables running from room to room and replace them later with custom made cables. You can even cut one end off of the pre-made cable, run it to the new location through a wall, ceiling, etc., and then attach a new Ethernet plug.)

The good news is that practically any Ethernet cable you would find to buy today is going to be the right type. As long the cables you purchase are rated at CAT-5, CAT-5e, CAT-6, or CAT-6e, you should be fine. If at all possible, get cables with a CAT-5e rating or higher, where the 'e' stands for "enhanced." CAT-5 would support most home networks (except those of you planning on having gigabit networking speeds [1000 Mbps] where CAT-6 and CAT-6e are more appropriate). CAT-5e cables (and above) also tend to be better made, so they put up with more abuse and last longer. Additionally, they are better shielded from electrical interference. Generally the rating will be prominently displayed somewhere on the package. Nowadays, it's pretty hard not to get at least CAT-5e rated cables. (There is a CAT-7 specification in the works as well.) You may also see the terms "Patch Cable" and "Straight Through." Those describe the same type of cable and are the type of cable we need to hook computers and other devices up to switches and routers (to be discussed in the next section).

One cable to watch out for will (hopefully) be labeled as a "crossover" cable. A crossover cable is made with the transmit and receive wires reversed on one end (hence, crossed over). That allows the cable to be used directly between two network devices without an intervening hub or switch. This means you can connect two computers together using only a crossover cable. (This cable is popular for hooking two Xboxes together, for example.) For most home networks, you will only need straight through cables. The exception I have seen to that is that sometimes a crossover cable is necessary to connect the DSL or Cable modem your ISP supplies to the DSL/Cable router that you buy. Many crossover cables are labeled or stamped with the word "Crossover" on the cable itself. Another way to tell - that I wish had be made a standard - is that crossover cables have red "boots" or red covers over the plugs on the end of the cable. (See the picture to the right.) Unfortunately, that's not standard and if you buy red cables they will probably have red boots and still be straight through cables. Ah, 'tis not a perfect world. Probably the easiest way to tell you've accidentally gotten a crossover cable is that when you use it to connect a computer to a router (or switch) none of the lights come on as if it wasn't connected. (Unfortunately, that's also the sign of a bad cable.)

Cable length is also another consideration. Pre-made cables come in lengths from 1 foot to 150 feet with typical numbers in between of 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 14, 15, 20, 25, 35, 50, 75 and 100 feet. The technical specification for Ethernet cablings cites a maximum of 100 meters or about 328 feet. In practice, you should try to have cables no longer than 150 feet if possible. If you must run a cable longer than 150 feet, you may need to put in an extra switch or hub (or repeater, but we won't get into what that is here) in order to maintain and amplify the quality of the signals.

If you need a cable that's 40 feet long, you can buy the next size up (50 ft) and just roll up the extra cable into a spool. If that seems a bit sloppy, one trick is to instead buy a 15 ft and 25 ft cable and join them with an inline RJ-45 connector like the one shown at the left. This connector has two female RJ-45 ports on either end. You connect two standard male to male cables into the jacks and end up with an extended Ethernet cable. Just make sure the coupler you use is made for Ethernet cables, is rated for at least as high of a transmission rate as the cables you are connecting to it (e.g., CAT-5e), and has all eight pins. (Just so you are aware, there are also crossover couplers, which turn two straight through cables into a joined crossover cable.)

Armed with this knowledge, (buy and) install the Ethernet cables running from each device to a centralized location. A good goal is to try to keep all the cable runs as short as possible. If you are planning a LAN, just pick a convenient point near the center. If you are planning on sharing a broadband connection, you would generally run all cables to wherever your broadband connection enters the house as it's logical to install your router next to the cable/DSL modem. That becomes your location from which to branch off your network. In either type of network you will run the cables to wherever your network hub or switch is. If you have decided to use multiple switches (or a combo router/switch and one or more other switches) route you cables from the device to the nearest and/or easiest switch possible. (See the next section.)

As a final bit of advice, if you are process of getting a new home built, strongly consider having most of the rooms pre-wired for Ethernet. Get the highest quality cable you can afford (e.g., CAT-6e) because it's much harder to run once the walls are finished. Have the wires originate (or terminate depending on your point of view) in a closet that is reasonably central to the house and that you will have easy access to. Mind the lengths of the longest cable and try to stay under 100 feet.

Switches + Network Wiring

Switches + Network WiringThe Network Hub/Switch

At this point, you've got Ethernet ports in some number of computers, gaming consoles, printers, etc. and a matching number of cables all coming from them to one location (or a few concentrating locations if you planned more than one switch). You now need a device (or two) that lets you connect all these cables together. For a LAN, that device is usually a stand alone Ethernet hub or Ethernet switch. For the broadband connection sharing network, that device is usually the cable/DSL router because most routers have a built-in switch (typically with three or four ports). If your cable/DSL router has only one port or you need to connect more devices than the number of ports on the back of the cable/DSL router, you will also need to attach a hub or switch to connect all your devices together.

The difference between a hub and a switch is analogous in the telephone world to the difference between a 3-to-1 telephone jack (the type of jack let's you connect a computer modem, a fax and a telephone to single telephone jack) and a full blown PBX. With a 3-to-1 telephone jack, only one of the telephone devices can use the phone line at a time (e.g., the phone, the computer modem or the fax machine, but not more than one). Similarly, a hub lets you connect all the devices together, but at any one time only one device can be talking to the other devices (e.g., another computer, network printer and the broadband connection) at a time. The hub blindly repeats the data sent from the device doing the sending to all the other ports on the hub in parallel. All other devices wanting to send data must wait until the network is free before they can transmit. This is just like having to hang up the phone in order to send a fax.

A switch, on the other hand, acts more like a telephone PBX. With a PBX, some of the telephones inside a business may be sharing some number of outgoing lines while other phones inside the business call each other at the same time. An Ethernet switch allows parallel connections between any two ports while leaving the other ports free to connect to each other if needed. For example, you might have one computer backing up files to another computer one two of the ports while at the same time the Xbox is playing a game online using the Internet connection through the router on two completely different ports. When it's first powered on, the switch doesn't know which devices (or other switches) are connected to which of it's ports. Initially, the switch acts like a hub. Let's say is gets a packet on port 1 with a source IP of 192.168.1.4. The destination/target IP indicated in the message is 192.168.1.7. The switch presents the packet it gets from port 1 to all the other ports. Let's say the response comes from port 3 (with the source IP address of the response being 192.168.1.7) The switch will remember that IP address 192.168.1.4 is on port 1 and 192.168.1.7 is on port 3. As more devices start communicating to each other, the switch learns which ports have access to one or more IP addresses on the LAN. After a while, it creates a map of which ports are associated with which IPs. Note that a single port may have multiple IP addresses mapped to it. We can connect one switch to another switch in order to expand the number of ports on the network. We talk about this topic in detail later in the section, Growing Your Network.

Perhaps thinking of a switch as a very fast, automated switchboard operator is a better analogy. The operator can connect any two phone lines together while the other lines remain free for other connections. Likewise, a switch allows any two devices on the network that connected to different ports on the switch to talk exclusively to each other while the other devices are free to use other pairs of ports to talk to each other at the same time. That's highly simplified and I haven't explained how the switch knows which two ports to connect at any given moment. I also haven't mentioned the limitations on the number of connections/hubs between devices that hubs have and switches do not. (Google the term "5-4-3-2-1 rule" if you are curious.) I won't go into more details because hubs are becoming rare in networks. The cost savings between a hub and a switch in the 5-port or 8-port versions is negligible. In some cases, hubs cost more than their switching counterparts because they have become rare.

As a side note: switches do not solve all networking woes. When you start downloading a big file from the Internet, little Billy playing an online game on his Xbox in the next room will become cannon fodder. This happens because even though your computer and Billy's may be attached to different ports on the switch, you are both trying to send and receive data via the same other switch port - namely the one that your router (and therefore, your Internet connection) is using. There is contention for that port. Downloading a file often takes a considerable portion of the bandwidth you have available, so there's nothing left for little Billy's game to use. Depending on the speeds of the network coming into your home, you might have to establish etiquette that requires checking to see what others are doing before downloading OS patches, game demos, news videos, or other large files.

In the shared broadband type of network, your cable/DSL router is probably also your switch. Therefore, your cables run to wherever your cable/DSL router is. The cable/DSL router is, in turn, typically near the cable/DSL modem. As was discussed in Example 2 of Planning Your Physical Network Layout, you don't have to locate your cable/DSL router next to your cable/DSL modem if that isn't a good place to concentrate the cables to. That said, ISPs are increasingly using an all-in-one combination cable modem, router, switch, and wireless access point in one device. In that case, you may not have a choice where the router's built-in switch is located. You can, however, buy your own switch and run a line from the ISP's device to that.

With the switch (or hub) powered on, begin plugging the cables into the ports. The devices you are connecting to the switch should also be powered up and their end of the cable plugged in to their respective Ethernet adapter's port. I find it's easier to understand this part by talking about a real-life device, so I am going to use a Linksys EZXS88W 8-port 10/100 Switch as an example. For each of the eight Ethernet ports that this switch has, there is a corresponding column of three lights. The link lights are the top row of green lights on this particular switch. At this time, that's really the only light we are worried about. Later, when we have the network set up and there is traffic flowing on it, the lights on the top row will flicker to indicate activity (data flowing to and/or from a device). As you connect each cable from a device to the switch, make sure the corresponding "link" indicator lights on the switch.

The second row of lights on the EZXS88W, labeled "100," indicates if the link speed is 100 Mbps (light on) or 10 Mbps (light off). The last row of amber lights, labeled FD/Col, indicate if the devices connected are capable of full duplex (light on) or half duplex communication (light off). In full duplex communication, the switch and the devices talking to it can both send and receive at 100 Mbps simultaneously. (The "FD" part of the label is an abbreviation for "Full-Duplex." The "Col" part is an abbreviation for "collision" and will turn red if and excessive number of collisions begins to be encountered at that port. Collisions are a topic for later discussion.)

You'll notice that not all columns have all have all three lights lit. The device connected to first port above (to the right of the green power light) is an older 10 Mbps half-duplex networked printer. Port 4, the device with only two green lights in its column, is going to the uplink port on an older 100 Mbps hub. The hub is capable of 100 Mbps transfers, but only in half-duplex mode (i.e., one direction at a time), which is why the FD/Col light is not on. Ports 6 and 7 have no devices connected to them at all.

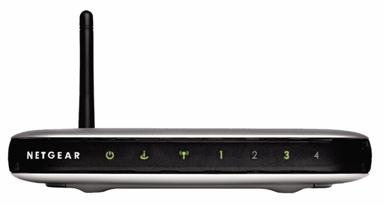

Keep in mind that the Linksys switch above is only one example. Different switches and routers will have different lights and use them differently. For example, on the Netgear combination router/switch (& wireless access point) shown here, there is only one numbered light for each of the four Ethernet ports. If the number is not lit at all, nothing is connected to that port. A 100 Mbps-capable device on port 1 makes the light glow green. A 10 Mbps-capable device would be indicated as such with an amber light. The number flickers to show network activity. Again, at this point, the goal is just to get the link lights to turn on for every device you hook to your switch. The cables all plug into the Ethernet ports, which in the case of the Linksys EZXS88W, are on the back as in the picture below.

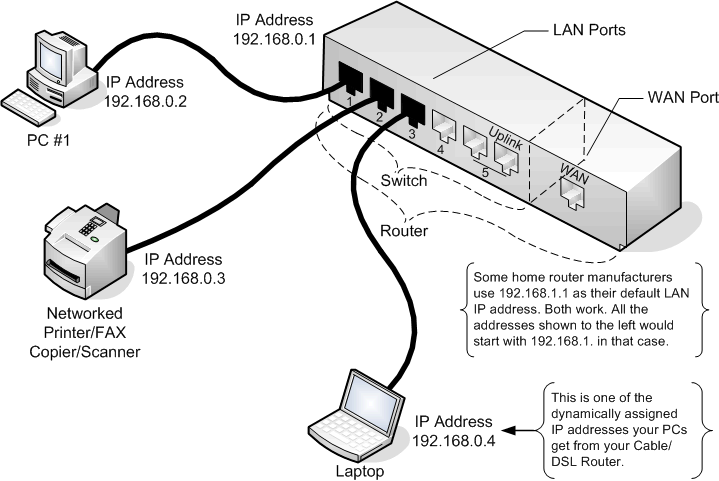

When all is finished, you should have made the basic connections needed for a Local Area Network. As mentioned previously, even if you are planning on only having a LAN now, you may wish to go ahead and buy a combination network router/switch. That way, if you later decide to add a broadband connection, you won't need to replace a switch with a router. Also, as we'll find out in the section on Configuring Your Network, the router provides some services that can make setting up a home network simpler. Either way, at this point we should have a network similar to the one represented in the diagram below. (Some of the concepts mentioned in the diagram, especially IP addresses, haven't been discussed yet. Just concern yourself with the wiring aspects now.)

The switch/router in the picture above is completely fictional, but is representative of common switches and routers. For one thing, switches often have a separate uplink port, but I've yet to see a router that has a one (on the switch portion, that is). The dashed rectangle signifies where the switch (or the switch portion of a combination router/switch) ends. From a physical perspective, the router only differs from a switch by the addition of a WAN port. The WAN port is almost always physically separated from the LAN ports, but that distance may only be a ½ inch or less. From a networking perspective, the differences between a switch and router are much greater (as we'll find out later).

Uplink Ports

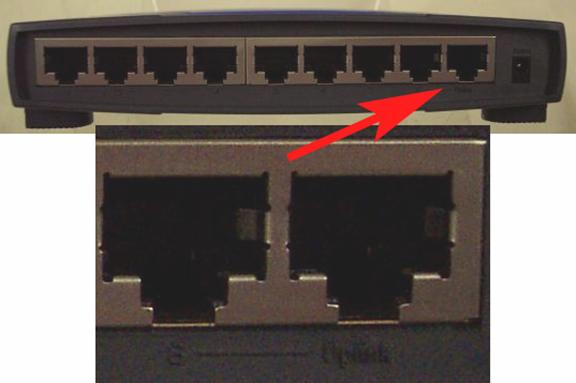

You should pay special attention to ports like port number 8 shown on the Linksys switch below, which is actually a pair of ports - one for uplink connections and one for normal connections. Uplink connections are used when connecting two hubs/switches or a router and a hub/switch together. Uplink ports are used when you are adding an additional hub or switch because you have run out of free ports. You plug one end of a straight-through cable into the new switch's uplink port and the other end into any normal port on the original router, hub, or switch (not the uplink port, if it has one). The special uplink port is just a jack with the transmit and receive wires crossed over, thus freeing you from having to purchase a crossover cable. Don't make the mistake of thinking that because the switch in the pictures has nine ports, it is a 9-port switch. Only one of the two ports at position 8 - either the normal or the uplink port - can be used at any given moment. If you do happen to plug cables into both ports, most routers will make one of the two operational and shut the other down. (Extra points given here for anyone that noticed a problem with the picture of the hub shown in the section Two or More Computers Sharing an Internet Connection found in the introduction. It shows cables plugged into every port including the clearly labeled uplink & normal port pair [port 1 on this one]. This will never work, but I guess it makes for a neater looking picture. The clip art was free, so I forgive them.)

Some switches don't use a separate port for uplink, but instead have a push in-push out toggle button that toggles one of the ports between normal and uplink modes. Switches with dedicated uplink ports or manually switched uplink ports are increasingly rare. Most recent switches don't have either, but instead have a "Medium Dependent Interface (Crossover)" (MDI [MDIX]) or "auto-switching" ports that automatically sense if they need to reverse the transmit and receive lines. A couple examples of one of these are the US Robotics USR7908 8 Port 10/100 Ethernet Switching Hub (A "switching hub" is the same thing as a switch.) and the Netgear Model FS605 5-Port 10/100 Desktop Switch. Netgear calls this feature "Auto Uplink." Don't get MDIX (or auto-switching) confused with "auto-sensing" (a.k.a. "auto-speed") ports. Auto-sensing refers to the ability to sense and adjust to the communications speed - usually either 10 or 100 Mbps. Almost all switches, hubs, and routers have the auto-sensing feature. There are also cable/DSL routers that are auto-switching only on the Wide Area Network (WAN) port (I.E., The port that connects to the cable/DSL modem. This same combination router/switch may or may not have auto-switching LAN ports

Typical Switches

The table below lists some typical wired Ethernet switches and hubs along with descriptions of some of their features. This section is becoming rather unnecessary as the switch has pretty much taken over for hubs at the same price point, and switching equipment has become even more ubiquitous than Ethernet adapters.

One question you need to ask yourself when buying a switch is how much you think your network will grow. If you already have three or four devices to hook up to a switch, an 8-port switch might make more sense than a 5-port one. (Don't forget things like a router, WAP and XBox in addition to laptops and desktop PCs when counting up the total.) On the other hand, there's only a little penalty for daisy-chaining another switch to your current one. Almost anywhere you can connect a PC or laptop, you can connect a switch and grow your network. (There are limits to this, but you're not likely to reach them in a home network.) See Growing Your Network.

| The Linksys EZXS55W is a 5-port 10/100 Ethernet switch. It uses a dual port configuration in the back for its uplink port. This switch has separate lights for link/activity, 10/100 connection speed indication, and full/duplex/collision indication. Linksys also makes 8-port (shown above) and 16-port versions of this switch. |

|

| The Linksys EG005 is a newer Linksys offering. It is a 10/100/1000 (Gigabit) Ethernet switch and functions much like the EZXS55W above, but at higher speeds. Rather than one (dual) port for uplink, all ports have MDIX sensing, so any port can serve as an uplink port without the need for crossover cables. Gone, however, are the individual lights for link, speed, and duplex mode. It has a single green LED for each port that lights steady when there is a link and flashes with activity. Linksys also makes an 8-port version of this switch, the EG008W. Both Netgear and Linksys make home (and small office) versions of their smaller routers with Gigabit Ethernet speeds. |

|

Gigabit Networking?

I've been asked often whether it's worth the extra cost to have gigabit Ethernet. Until recently, my response was that if you're talking about pulling/running cable in walls then yes, put in gigabit Ethernet capable wire (Cat 6e or better). However, as far as the equipment, it could be swapped out at any time with minimal effort. So basically, I've been saying run the best cable you can afford, but if you have existing 10/100 Mbps equipment, just stick with that. My thinking here is that the cost of installing cable is a hefty portion of the cost and effort of getting a house wired for networking. It's much more difficult (and often practically impossible) to do after the walls are up. If you're going to run wire, run the best you can afford; it's not something you want to do again. You should also consider Cat 7e and fiber.

I don't constantly backup huge files over my home network and the difference between waiting 5 minutes or 1 minute to copy that big file doesn't mean that much to me. LAN and Internet games over our home network are plenty fast. There's been no "killer app" to drive me to gigabit Ethernet, yet. Technically, there still isn't a killer app, but I can now see a couple in the wings. Interestingly, it's not online gaming, which is what I thought it would be. Instead, it's streaming video and other variations of video on demand. Already, I can stream video to my TiVo DVR from Netflix and Youtube. I can buy movies from Amazon and download them. Most of these are not HD quality .. yet. What is needed is a higher-speed network from the ISP to the home than is typically available. We're not there yet, but it's coming.

My neighborhood has 16 Mbps downstream (incoming) cable Internet service available from Comcast and Verizon FiOS is available at speeds up to 50 Mbps downstream by 20 Mbps upstream. At those speeds, standard definition and DVD quality video on demand are quite doable. Rather than running to WalMart to purchase a DVD, we can just download it to a family "media & file server." Then we could either burn a DVD or just stream it to one or more network enabled HDTVs, DVRs, or PCs. When this becomes common and video quality goes to the High Definition (HD) level, I'm going to want/need to move & stream files the size of DVD movies from one device to another. In that scenario, gigabit Ethernet makes sense.

Most motherboards and desktop computers are now coming with built-in gigabit Ethernet, so hooking them up is essentially "free." The cost of the gigabit switches is now only negligibly more than the cost of 10/100 Mbps switches. In fact, 10/100 switches are on getting harder to find. My advice now is if you are putting in a new network, go with gigabit Ethernet equipment. If you start doing a lot of HD video streaming on a 10/100 network, now is probably the time to upgrade.

Wireless Equipment

Wireless EquipmentWireless Networking Equipment

At first blush, the wireless network would seem to be the holy grail of setting up a small office or home network. There are no cables to run through walls, attics and crawl spaces. Second, the current (advertised) wireless networking speeds are rated at or near the typical wired network speeds. (The draft 802.11n specification has a theoretical maximum around 600 Mbps. Early wireless solutions were also more expensive, but today's wireless equipment is fairly inexpensive - often coming close to the price of wired equipment. In fact, it's becoming difficult to find a router that does not include wireless capability.

So, why hasn't everyone thrown their cables away and gone wireless? That's really a large topic in its own right, but we'll just touch on a few issues for now. For one thing, the theoretical maximum and the typical maximum have a vast gap. Wireless data is usually encrypted (except in public wireless "hot spots") which adds overhead. The wireless protocol itself is not the most efficient. Also, since every wireless device can "hear" every other wireless device in range, there tends to be more contention for and collisions on the network. That reduces the effective throughput of the network if more than a few wireless devices are present. That said, there's something to be said about working on a laptop on the deck on a sunny spring morning. In the next sections, we look at special considerations for planning a wireless network and the initial configuration of the radio wave medium.

For a wireless LAN, there will need to be some form of a Wireless Access Point (WAP) as part of the network. (See the section, Special Considerations When Planning a Wireless Network.) The most common version is in a combination switch/router/wireless access point. However, standalone WAPs can be used in place of or in addition to one in the router. As part of the planning stage discussed earlier, the decision whether to buy a single, combination router, switch and WAP device or instead purchase separate router/switch and WAP devices should have been reached. If you're planning a purely wireless LAN, a WAP is all that is needed because it will serve as the "switch" for the network. You will need a wireless Ethernet adapter for every device to be connected wirelessly of course. Most new laptops come with a wireless Ethernet adapter built-in, but few desktops come with wireless. Fortunately, it's as easy to add as any PCI card or USB device. The table below has a few pictures and descriptions of some typical wireless local area network (WLAN) equipment.

| To the right is the Linksys WRT54GL, a combination DSL/cable router/firewall, Wireless Access Point (802.11g - 54 Mbps), and 4-port 10/100 switch. Its front has LEDs for the WAN (Internet) connection, the WLAN (Wireless LAN), and each port of the built-in 4-port 10/100 Ethernet switch (LAN ports). The two wireless Ethernet radio antennas can be seen from the rear. This version of this router is most notable for the fact it is built on a Linux kernel. Several alternate kernels such as DD-WRT and Tomato have been developed for this router that adds features such as the ability to use the router as a wireless bridge (see below) and set Quality of Service (QoS) settings for different types of network traffic. |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The back of the WRT54GL shows the connection for the WAN (i.e., the Internet connection from your cable/DSL router), a reset button, four 10/100 MDIX ports that make up the switch, and the power jack. This is a pretty typical setup for a combination router/switch/WAP device. |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The WNR834B is one Netgear offering of a combination router, four-port 10/100 switch, and an 802.11n (draft version 2) WAP. The 802.11n specification has yet to be formally ratified, but units such as this one built on the version (1 and) 2 draft specification are available. For the best chance of obtaining compatibility and function with wireless N devices, I recommend sticking with equipment from one manufacturer. That is, if you buy a Netgear 802.11n router, try to buy Netgear 802.11n wireless adapters for any laptops and desktops that need them. |  Copyright 2010 Netgear Corporation |

The back of the WNR834B router looks much like that of Linksys' WRT54GL if not a bit more colorful. However, there is one thing to note the absence of, and that is, any antennas. The new 802.11n compatible routers are using internal antennas. This is both good and bad. Good in the sense that the antenna won't get caught on anything. Bad in the sense that the antenna can't be removed and replaced with a directional antenna (like the "Cantenna") for boosting the signal range.

The back of the WNR834B router looks much like that of Linksys' WRT54GL if not a bit more colorful. However, there is one thing to note the absence of, and that is, any antennas. The new 802.11n compatible routers are using internal antennas. This is both good and bad. Good in the sense that the antenna won't get caught on anything. Bad in the sense that the antenna can't be removed and replaced with a directional antenna (like the "Cantenna") for boosting the signal range.

| The WAP54G is a WAP-only device used to add or extend wireless networking to a LAN. The front of the WAP54G looks much like the front of the WRT54GS, but with fewer lights. Since it has no router or switch capabilities, it has no indicator lights for the WAN or the switch ports. One interesting feature of the WAP54G is that it can be made to operate in "client" mode, which turns it into a wireless bridge (for a lot less money than the specialized WET54G wireless bridge shown below). Not all WAPs have this feature. For a LAN network, a WAP-like this is sufficient. |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The back of the WAP54G looks very different than the WRT54GS. There is only a jack for the power adapter and a single Ethernet port for attaching the WAP to the wired network. The WAP54G is intended to be an add-on device to an existing wired network. |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

The paragraphs above showed some wireless access point (WAP) devices either as a standalone device or in combination with a router/switch. The next several paragraphs show the other side - wireless Ethernet adapters. Note that most laptops now ship with some sort of built-in wireless Ethernet adapter, so you may not need to purchase anything at all for those. On the other hand, almost no desktops ship with wireless capabilities, so a PCI or PCI-e add-in card like those shown below will be necessary.

| The Netgear WN511B is the 802.11n counterpart WNR834B router shown on the previous page. It is backward compliant with 802.11b and 802.11g as well. Even if you have a laptop with a built-in wireless network adapter, it may only be 802.11g compatible. If so, this card can be used in a laptop's PCMCIA/Cardbus slot to add true wireless N speeds. |  Copyright 2010 Netgear Corporation |

| The Linksys WMP54G is a PCI wireless Ethernet adapter for desktop PCs. It installs into a PCI slot just like wired PCI Ethernet adapters. This particular adapter supports a 54Mbps 802.11g transfer rate as well as well as Linksys' proprietary SpeedBooster technology. |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The Netgear WN311B shown here is the PCI card version of the WN511B shown above. It supports 802.11b, 802.11g, and 802.11n. One thing that is notable about this card is the separate antenna case. This allows the antennas to be mounted away from the signal-killing, metal PC case that most desktop computers have. |  Copyright 2010 Netgear Corporation |

| The WUSB54G is a USB adapter version of Linksys 54Mbps wireless technology (802.11g). Wireless adapters like this one can be used to connect USB-capable devices to the network without the need to insert or install a network card like the previous two examples. It's a solution for those who don't wish install a card like the WMP54G in their desktop PCs and for other devices that have USB ports but no PCI slots. However, make sure that your USB ports are version 2.0, not 1.1. The throughput of these adapters on USB 1.1 ports is disappointing. |  WUSB54G USB Wireless Ethernet adapter Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The WUSB54GC is a compact version of a USB wireless Ethernet adapter. These work fairly well with notebooks, but I've found them to be disappointing with desktops. This is probably due to the small antenna size and the fact there is a relatively large metal case right next to them, which may be between the adapter and the wireless access point. |  WUSB54GC Compact USB Wireless Ethernet adapter Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

In addition to the standard wireless access points (WAP) and wireless adapters, there are a number of special purpose wireless devices. Several of these are shown in the next few paragraphs, but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

|

The Linksys WRE54G wireless range extender does what it sounds like. It extends the range of your wireless network by retransmitting the wireless packets it receives. The retransmitted network traffic is sent at full power. If some of your wireless devices are getting a poor or no signal in some areas you would like to use them, a range extender can be placed at a point between the WAP and the receiving wireless device to boost the range of your wireless network into that area. One note, however, is that devices like wireless range extenders and wireless bridges (shown below) work best with (and sometimes only with) other equipment from the same manufacturer.

|

Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The Linksys WET54G shown to the right is a wireless bridge. This device allows the connection of two wired networks over a wireless connection. This device is useful in the situation where there are groups of wired devices in two locations, but running a wire between them would be difficult. One end of the bridged network is the standard WAP or combination router WAP discussed before, and the other end would be a wireless bridge like this WET54G. A bridge like this also useful for connecting devices that have wired networking capability like a TiVo DVR or PlayStation 3, but don't have a wireless adapter available. It can be used with any device that has a standard Ethernet port. Earlier versions of this bridge included a 5-port switch, but this version includes only a single Ethernet port. If there is more than one device on the bridged end, a separate switch can be attached to the bridge. In the wild, however, this box is pretty pricey. It may be cheaper to buy the dedicated WAP like the WAP54G, which can be run in bridge ("client") mode. (It also only has a single Ethernet port.) |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| The Linksys WET610N shown to the right (front and back) is an 802.11n version of a wireless bridge. This bridge has the advantage of using the faster wireless N networking, but the disadvantage of only offering internal antennas. In general, the range of wireless N devices is superior to wireless G (802.11g) ones. However, it's sometimes necessary to employ a unidirectional antenna of some sort to extend the range. (See the discussion in the Linksys WRE54G description above.) That's not possible with this model unless the user opens and modifies the unit (thus voiding the warranty). |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

| Another device for wirelessly connecting game consoles like the PlayStation 2 and the Xbox 360 is the Linksys WGA600N. This is a specialized version of a wireless bridge of the WET610N above. If you have friends over with their consoles, you will need to plug a separate switch into the WGA600N (or the WET54G) and then plug the consoles into the switch. The advantage of this box over the WET54G is that it runs at 802.11n speeds if your router/WAP is also running at that speed. |  Copyright 2010 Linksys Corporation |

Here are a few hints for choosing your wireless networking equipment. If the location you've chosen for the router also happens to be reasonably close to the area you wish to serve wirelessly (where "reasonably close" is in the area of a 40 foot radius from the router in all directions [including up and down]), a combination switch/router/WAP device should work well. This is what most people will probably choose. On the other hand, if the wireless devices are going to be far from the router/switch (assuming you have a router/switch), you may want to invest in a separate router/switch and WAP. In this scenario, the router/switch is placed in a location near to your ISP's equipment (e.g., cable or DSL modem). Then a cable can be run from there to the WAP in another part of the house as necessary. If you can't cover the area you wish with a single WAP (or a combination router/switch/WAP), consider purchasing a second WAP or Wireless Range Extender. If you already have a router/switch for a pre-existing wired network and you are just adding a wireless LAN, a new, separate WAP makes sense if it lets you get the WAP closer to the area to be served wirelessly. Otherwise, you may want to purchase a new combination router/switch/WAP to replace your existing wired router/switch.

I recommend buying all the wireless equipment from one manufacturer. I've had reasonable luck mixing equipment from different manufacturers, but I still prefer to be homogeneous when it comes to wireless networks. Even though 802.11b, g, and n wireless networks are standards, they haven't been in existence nearly as long as wired networks and not all the kinks have been worked out. This is especially true with 802.11n equipment. The standard for 802.11n has been finalized but is still somewhat new. Some manufacturers' equipment just won't play nicely with other manufacturers' equipment. Additionally, if you plan on using a manufacturer's "enhanced," "turbo" or "boosted" mode to go beyond the rated wireless spec, you must purchase the equipment from the same manufacturer. Those speed enhancements are proprietary to the manufacturer. In addition, some manufacturers' shut off their proprietary speed enhancements if any equipment without the speed enhancement capability is detected in the range of the WLAN. This is because the manufacturer wants their equipment to be compatible with the standard wireless speeds, and may not be able to support both the standard speeds and the proprietary-enhanced speeds simultaneously.

Setting Up the Network

Setting Up the NetworkConfiguring Your Network

Now, we get to the fun part! Up to this point, we've run the wires (and/or configured your wireless connections) and hooked the underlying network together to your switch, router and/or WAP. We have link lights (or the equivalent) on every wired and wireless device. (Right?) Even with all that, we so far have only provided a stable medium - for the wired network anyway - upon which the network can communicate. We (may) still need to configure each device on the network in order for them to listen to each other.

A wireless network has an additional step that a wired network does not. To connect to devices on a wired network, only the proper cable is required. A wireless network uses radio wave rather than a cable as the transmission medium. The wireless transceivers used in both the WAP and Wireless Ethernet Adapters must be configured before the standard configuration can be done. That's the topic of this and the next several sections.If you are trying to configure wireless network equipment - especially if the equipment is not from the same manufacturer - you may need to skip ahead to the section on the configuration of the wireless equipment.

Using DHCP

Using DHCPUsing DHCP IP Address Assignment for Automatic Configuration

If your network is connected together by a combination router/switch/WAP, the simplest way to set the IP addresses for the other devices on the network is to have them get their IP addresses using DHCP. The term "DHCP" stands for Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol. It is a network protocol that does pretty much just what it sounds like - it dynamically configures hosts (i.e., devices) on the network. Most routers include a built-in DHCP server, and it's usually turned on by default. If you are configuring a standalone network using only a switch, you probably don't have a DHCP server available and should skip to the section titled Fixed/Static IP (Manual) IP Assignment.

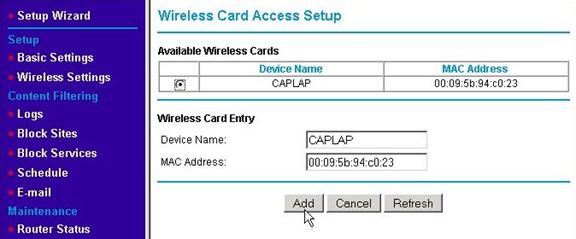

When a device wants to connect to a network and wants to get its network settings dynamically using DHCP, it will broadcast a network-wide message (with its MAC address included, since that is the only unique number it has at that moment) asking for a DHCP server to lease it an IP address and other settings. If your WAP/router has a DHCP server and it is enabled, it will respond to the request with an IP address and other network settings like the network mask, network gateway IP address (which is usually the LAN IP address of the router itself since it is the gateway to the Internet) and the IP addresses of one or more DNS servers. It also includes the length of time that the DHCP server will reserve that IP address for that device. That is called the "lease" time of the DHCP request. Devices that are configured using DHCP are called "DHCP clients." If you have no DHCP server for your LAN or it is not turned on initially, you will have to set the IP addresses manually. A DHCP server is never required, but almost all home routers do have a DHCP server and they are quite convenient. If you are setting up a LAN without a shared broadband conenction, you may still want to consider including a router with a DHCP server just for this convenience. (There are cases, however when you want a particular computer to always have the same address. See the section Fixed/Static IP (Manual) IP Assignment for the discussion on that topic.)

I'd like to offer one word of caution here (because it's been done a number of times based on what I see on the networking forums). If you first buy a router without a WAP (or your ISP supplies you a router without one) and later wish to add a second router with a WAP (because the combo router/switch/WAP boxes are often cheaper than standalone WAPs), you will need to turn off the DHCP server on the new router (or at the very least configure it to serve a different range of IP addresses). If that is not done, which of the DHCP servers will answer a request for an IP address will be potentially random. This will result in machines on the network getting duplicate IP assignments if the two DHCP servers on the network assign an overlapping range of IP addresses.

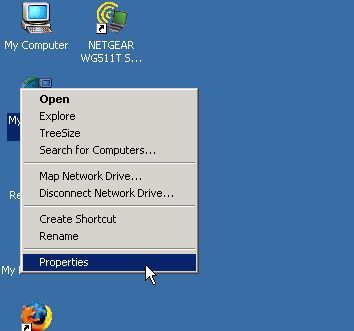

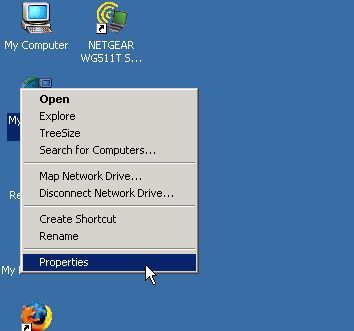

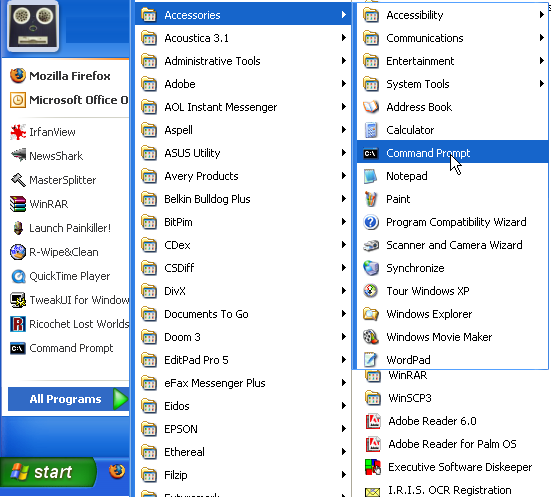

Setting an Ethernet adapter to use DHCP is very straightforward. The following example uses the Windows 2000 operating system, but the other Windows OSes are similar. First, right-click on the "My Network Neighborhood" icon on your PC's desktop. Choose the Properties menu item from the pop-up menu as shown here. In Vista, go to the Start menu and choose the Control Panel. In the Control Panel, choose Network and Sharing Center. From the Network and Sharing Center, choose Manage network connections from the list of tasks on the left.

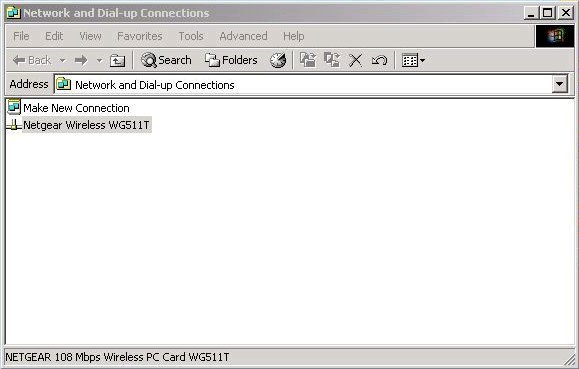

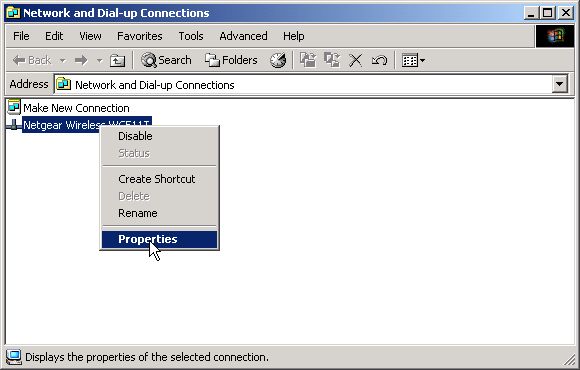

This will bring up the Network and Dial-up Connections window as shown below. In Vista, this is called just "Network Connections." (Since I sometimes use my laptop with a wired network card and with a wireless card at other times, I renamed the wireless Ethernet adapter to "Netgear Wireless WG511T" so I know at a glance, which one I have plugged in. If you would like to rename your network adapter, left-click on its icon and choose "Rename" from the pop-up menu.)

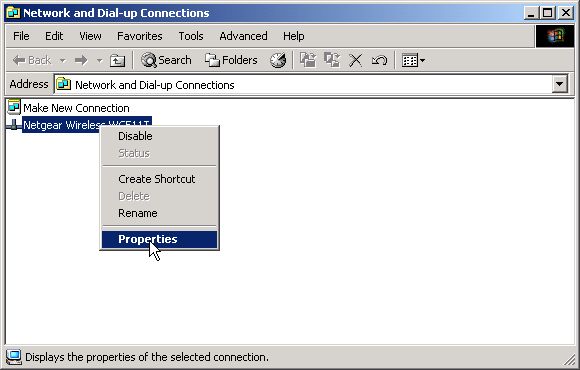

Left-click on the network adapter, which will usually be named something like "Local Area Connection" by default. This will bring up a pop-up menu. Choose Properties from that menu as shown here.

This will bring up the Properties dialog for your Ethernet adapter. Select the Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) from the components list (you may have to scroll it to the bottom) and click on the Properties button. (Double-clicking the Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) line will have the same effect.)

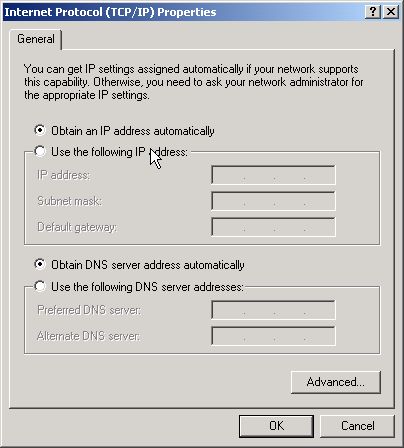

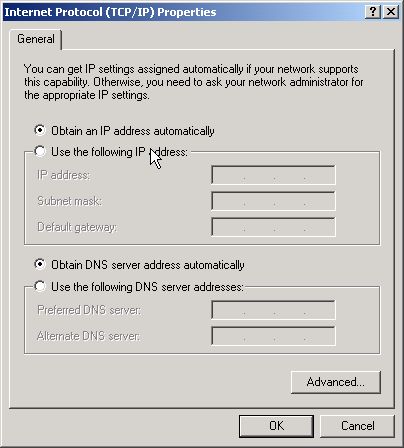

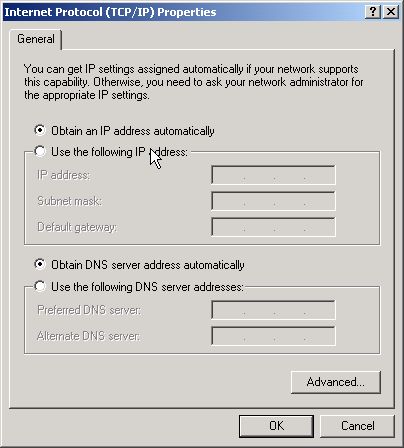

The Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) Properties dialog box will appear as shown below. On that dialog and under the General tab (which is the only tab), choose the radio buttons to Obtain an IP address automatically (i.e., get an IP address from a DHCP server) and Obtain DNS server address automatically (i.e., also get those IP addresses from the DHCP server).

Click on the OK button. With Windows 2000, you sometimes have to reboot after making such a change. With Windows XP and Vista, you almost never need to reboot after changing the IP address. Repeat the above steps for your other wireless devices.

Repeat the above steps for your other networked devices.

Welcome back (if you had to reboot, that is). Now, it's time to see if we got what we expected. We should now have basic connectivity between all the connected devices and the WAP. We can check this using Test 4: Checking for Valid IP Address and Test 5: The Handy-Dandy LAN Ping Test. Try those tests now and then move on to the next section.

Changing DHCP Server IP Assignment

Changing DHCP Server IP AssignmentChanging the DHCP Server's IP Assignment Range

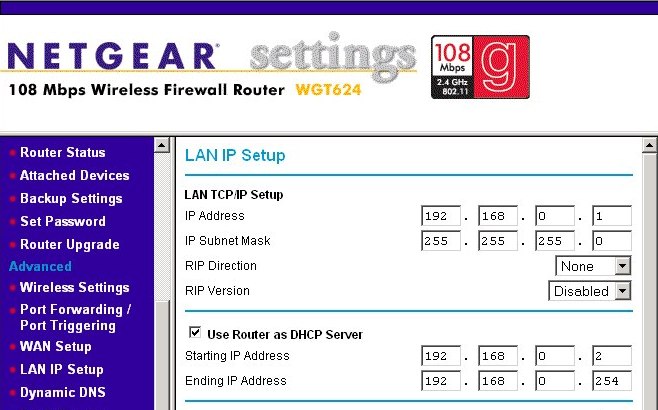

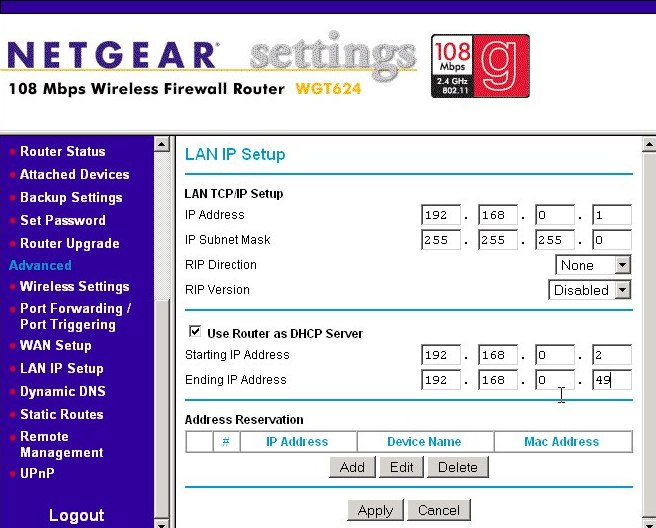

By default (at least in the case of the Netgear WGT624), the full range of LAN IP addresses is given to the control of the DHCP server. That is, all the addresses from 192.169.0.2 through 192.168.0.254 (where 192.168.0.1 is reserved by the router for its LAN IP address) are handed out by the DHCP to clients as they are requested. If we need to reserve some addresses for fixed IP assignment, we need to wrest a few of those away from the DHCP server's control. In order to do that, we need to change the configuration of the DHCP server in our router. As with anything dealing with changing the configuration of the router, first we log in.

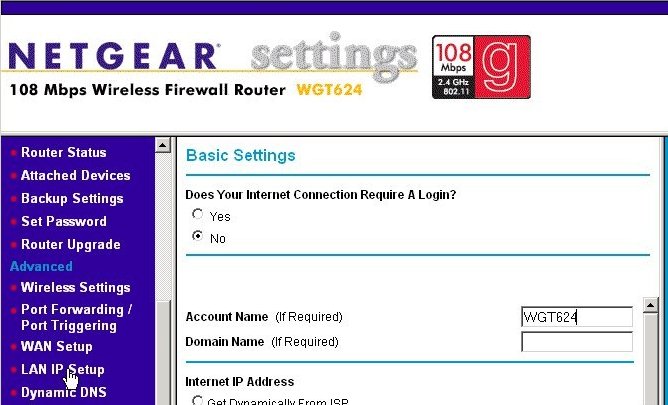

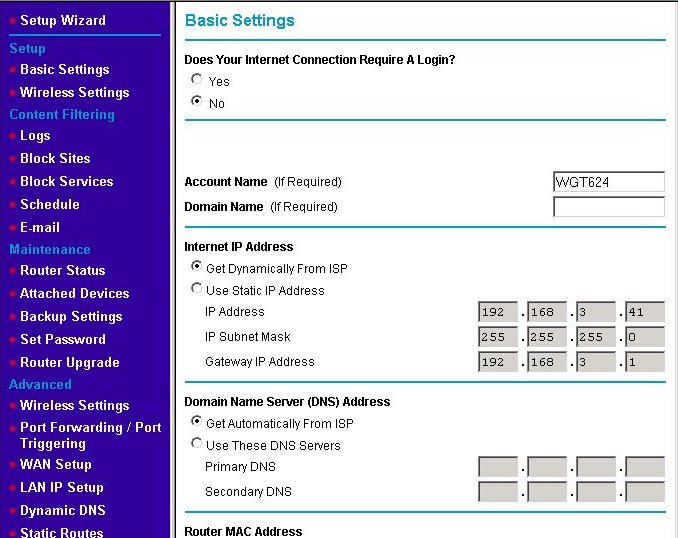

That will bring us to the first (Basic Settings) page. We need to go to the page where the DHCP settings are. On the Netgear WGT624, that is found on the LAN IP Setup page, so we click on that.

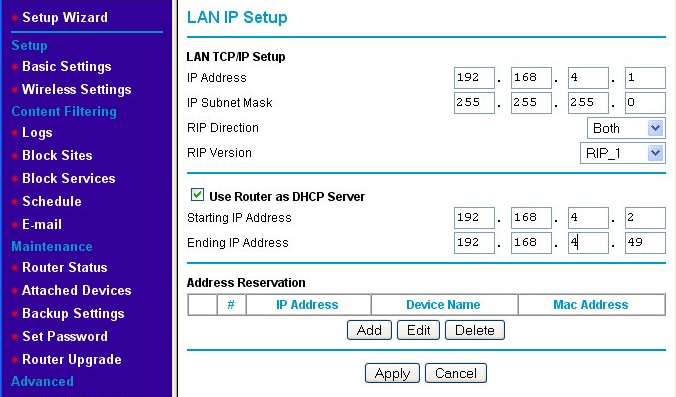

The LAN IP Setup page is shown below. We click on the last text box on the Ending IP Address under the Use Router as DHCP Server section, so that we can change the value from 254.

For the example shown below, we change the Ending IP Address to 49. That means your DHCP server will hand out IP addresses from 192.168.0.2 through 192.168.0.49, inclusive or 48 addresses in total. That should be enough for most home networks, but you can always bump it up later. These IP addresses are only given to devices attached that ask for automatic configuration - that is, devices that act as DHCP clients. You'll also notice a setting for the IP Subnet Mask on the page below. That will also be given to your client as well as the Domain Name Server (DNS) Addresses (if any), which on this router are found near the bottom of the Basic Settings page.

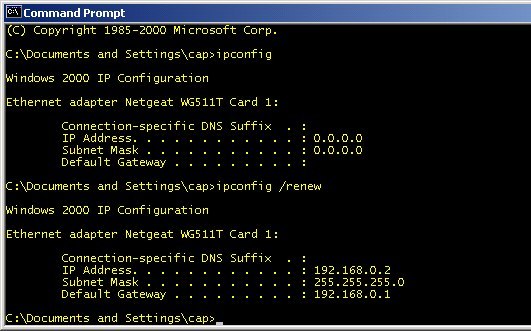

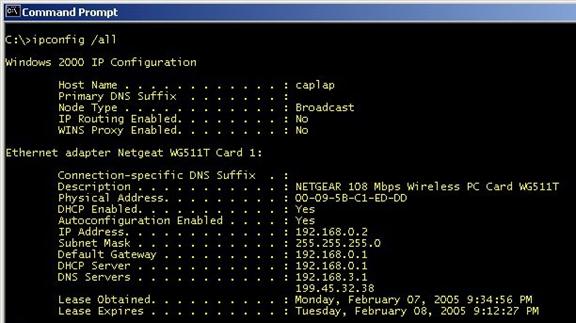

When you have the configuration numbers set the way you want, press the Apply button. If the machine you configured the router from happens to also be one of those DHCP clients, an interesting thing may or may not occur at this point. You may loose your connectivity to the network. The basic troubleshooting from Test 4: Checking for a Valid IP Address is to check to see if you have a valid IP address. Sometimes when you are fooling around with the DHCP Server settings and you are a DHCP client, you'll find yourself with no IP address after you apply the change. This state is shown in the first ipconfig command's results below. The situation is (usually) easily recoverable. Just as the DHCP server for a new IP address. Just type in the command ipconfig /renew as shown in the bottom half of the screen below and the DHCP server should give you a new IP address. The renew option will make your machine send out a DHCP request for a new IP.

I haven't determined what causes the loss of the IP address you already had, and it doesn't happen every time the DHCP server's settings are changed. (At least, not in my experience.) It's a mystery. Oooh!

Changing the Router's Internal Network

Changing the Router's Internal NetworkChanging the Router's LAN (Internal) Network Number

This section is totally optional and used for fixed (static) as well as when DHCP is being used for IP assignment. If you're brand new to home networking, I suggest skimming it for now, but not actually performing the changes. You may want to come back to it later when you are more comfortable with your home network. Also, if you add a second (or third) router to your network, you will likely have to perform the changes given here.

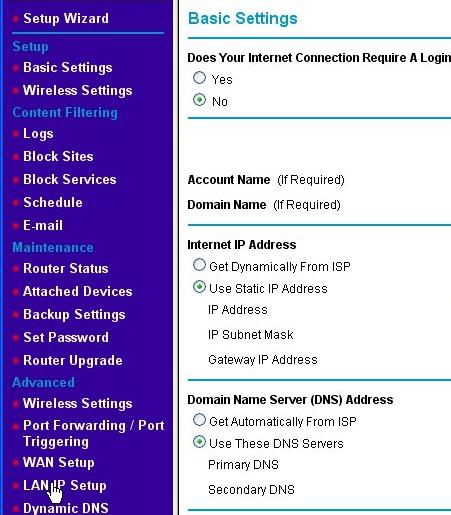

You can also change the LAN's network number - which is the beginning portion of all the devices on your LAN. We're going to stick with 192.168 as the beginning two "octets" of the IP address. There are other valid values for that part, but we'll leave that discussion as an exercise for the reader. To change the network number of your LAN, first login to the router, and then click on the LAN IP menu. (This will be different for a different brand of router.)

The original settings on the Netgear WGT624, as shown below, have the LAN IP address set to 192.168.0.1. (Linksys uses 192.168.1.1 as their default.)

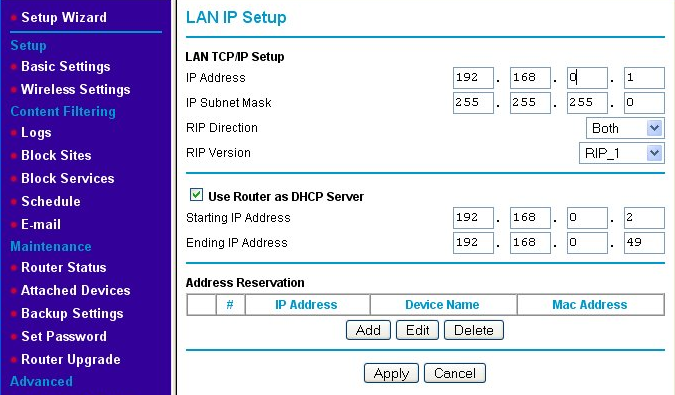

In our example, we'll change the network number from 192.168.0 to 192.168.4. Change the third field of the LAN TCP/IP Setup, IP Address from 0 to 4. The new gateway address for the devices inside your LAN will be 192.168.4.1. You also need to change the IP addresses that the DHCP server is lending out to be in the same network - namely, the 192.168.4 network. To do this, change the third fields in both Starting IP Address and Ending IP Address to match the setting for the LAN IP Address, which in our example is 4. When you've set those three fields, the result should look like the screen below.

Once you press the Apply button, your network number will be changed. You many need to issue an ipconfig /renew command in a Command Prompt window (See the example in the section Changing the DHCP Server's IP Assignment Range.) so that the devices that are DHCP clients get a new address in the new network number's range. (For devices like an Xbox 360, you may have to cycle power to get them to lease a new IP address on the new network.) If you have set any IP addresses manually (i.e., Fixed or Static IP addresses as explained in the next section), you also get the pleasure of resetting them manually. (The same is true if you've set any firewall rules for machines at a fixed IP address.) We talk about fixed (or static or manual) IP address assignment in the next section.

Fixed/Static IP (Manual IP) Assignment

Fixed/Static IP (Manual IP) AssignmentFixed/Static IP (Manual IP) Assignment

Technically, you don't need a DHCP server anywhere on your network; it's just a convenience. You can manually assign the addresses of all the devices on the network. In the beginning of TCP/IP networking, there were no DHCP servers and no DHCP protocol. All device addresses were set manually. There's a bit of comfort in having complete, manual control over your network's configuration. Still, using fixed IP addresses can be a bit of a chore if you change your network very often. While that's less typical in most home networks (excluding at least my own home network), it's very typical in offices as employees move, projects add/remove hardware, etc.

If you are setting up a Local Area Network using only a switch (and no router) to connect the network together, your only option (short of installing a DHCP server on one of the networked computers) is using fixed IP addresses. It's also very typical, even if you are using DHCP, to reserve some portion of the IP address space on your network for devices that need a fixed IP address that will be reserved for that device "permanently." A very common reason you'll need this is to be able to set up firewall rules necessary to let some online games work. That is, you will set up a rule in your router's firewall to allow certain types of network traffic to pass through to a particular machine by specifying the IP address of that machine. It's desirable that the machine's IP address doesn't change over time so that you don't have to periodically edit the rule(s) to match. However, when a machine uses DHCP, there's no way to guarantee its IP address won't change; in fact, it's pretty certain that it will at some point. In this case, giving that machine a fixed IP address is the way to go. (I'll use the terms "static," "fixed," and "manual" interchangeably in this section.) Another common device to give a fixed IP address is a networked printer. Many of the printer drivers installed on computers will have trouble locating a printer if it's IP address changes. It's best to assign a fixed IP address to a networked printer.

In the section Changing the DHCP Server's IP Assignment Range, we configured the router to use only part of our internal LAN IP address space. In that example, 192.168.0.1 is reserved for the router itself to use, so that we have a fixed gateway address. The DHCP server hands out addresses from 192.168.0.2 through 192.168.0.49, inclusive. What happens to the rest of the network addresses - those from 192.168.0.50 through 192.168.0.254? (192.168.0.255 is reserved for network broadcast messages.) The answer is "Anything we want." Those addresses have been made available for fixed IP address assignment for those devices that need such a thing. All we need to do is make sure we don't reuse an IP address more than once and that the ones we choose to be fixed are outside of range of DHCP server, but still on the same network.

Setting a static IP address for an Ethernet adapter is a variation on setting up the DHCP configuration. On the machine that we wish to give a fixed address, we start by opening up the network properties by right-clicking on My Network Places (or Network Neighborhood) and choosing Properties from the pop-up menu.

Next, we pick our Ethernet adapter from the list. (Here, I've renamed my wireless adapter to "Netgear Wireless WG511T." By default, yours will probably be named "Local Area Connection.") Right-click on the adapter name and pick Properties from the pop-up menu. (Alternatively, you can double-click on the adapter's name and press the Properties button from the Local Area Connection Status dialog. [Not shown here.])

From the Properties dialog for your Ethernet adapter (as shown below), pick the Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) entry from the components list and click on the Properties button. (Double-clicking on the Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) component name yields the same result.)

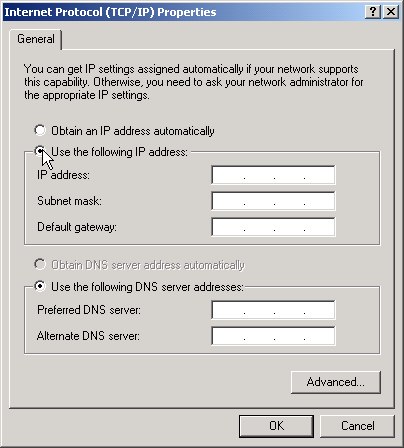

If you have been using DHCP prior to this or the Ethernet adapter is still set at the default settings, your Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) Properties dialog will probably look like the one below.

What we want is to specify a particular IP address for our adapter. To do this, click on the Use the following IP address radio button. That will enable the IP address, Subnet mask, and Default gateway text fields. It will also enable the Preferred DNS server and Alternate DNS server text fields and disable the Obtain DNS server address automatically radio button. (See the following screen.)

Enter the IP address you've chosen for this Ethernet adapter into the IP address text area. In the example below, 192.168.0.100 was chosen. Place your cursor before the first period and type "192" into the first text area of the IP address. Because 192 fills up the area, the cursor automatically advances to the second text area. Type "168" into that text area and the cursor will automatically advance again. Next, type "0" into the third text area. This time, the cursor does not automatically advance because 0 does not fill the (three character) area. Press either the right arrow or press the period key to advance to the next and final IP address field. Finally, type "100" into the fourth IP address field.

Press the tab key to move to the Subnet mask text area. Without explanation, I'm just going to tell you to type "255," "255," "255" and "0" into the text fields. (The cursor will automatically advance on the first three.) Exactly what the subnet mask does is beyond the scope needed for setting up a small network. Search for subnet mask if you wish to know more.)

The Default gateway is set to the IP address that is reserved for the router on the network. The example below assumes we have not changed the default and "192.168.0.1" is entered using the same entry method as for the IP address.

The values for the Preferred DNS server and Alternate DNS server are generally given to you by your ISP provider if you are setting up a Broadband Connection Sharing network. These will be the IP addresses of the DNS servers they provide for your use. If your router uses DHCP to get an IP address from your ISP (in the same way that your DHCP clients get IP addresses on the internal LAN from your router), the DHCP response will include the preferred DNS servers. Therefore, you should be able to look at the basic network settings screen of your router to see what addresses to copy to the fields below. If you are setting up a LAN, you can leave these entries blank.

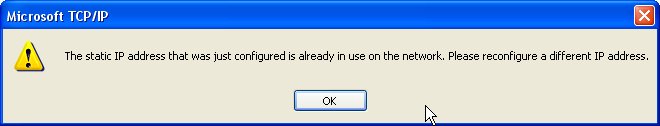

Once these entries are completed in a manner similar to the one above, click on the OK button. The typical response is that the Window takes a few several seconds or a minute to close. (On older Windows operating systems prior to XP, you will be asked to reboot. Do so if asked and continue from this spot.) If you see a warning message similar to the one below, it means you have accidentally assigned the same fixed address to two (or more) networked devices. Change one of the IP addresses so that each machine has a unique one. Typically, the other machine at that IP address will display a message that some other device is attempting to use its IP address.

That's it for setting a fixed IP address.

Configuring Wireless

Configuring WirelessConfiguring the Wireless Access Point and Wireless Ethernet Adapters

Once you have decided on the wireless equipment you will use, the next hurdle to overcome is configuring equipment to work together. With a wired network, there is no configuration of this sort. We can plug almost any cable into any hub, switch, router, or Ethernet adapter and be fairly certain a link will be established between the two devices. With wireless networking, this is not (yet) true. The radio medium must be configured before the equipment will exchange any data with each other, and this must be completed correctly before the network configuration can be completed (which was discussed in Configuring Your Network).

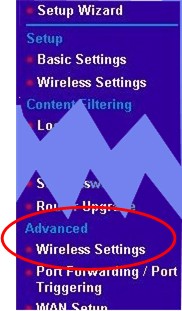

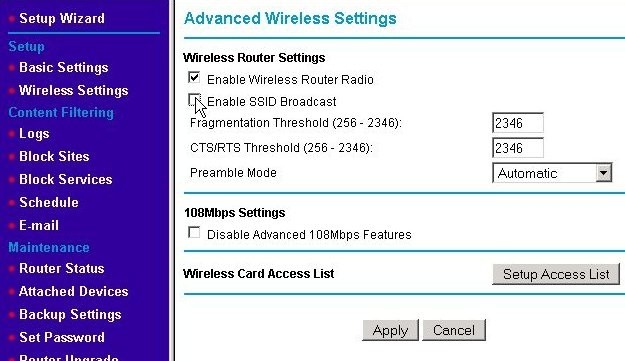

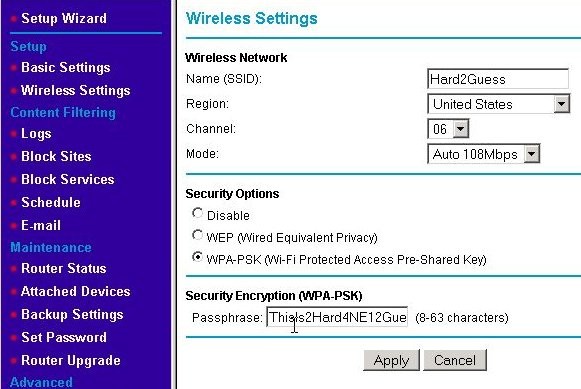

The specific WAP used as an example here is a NetGear WGT624-V2 combination router (with firewall), 4-port 10/100 switch, and 802.11g (54 Mbps) wireless access point. Is also features Netgear's proprietary 108 Mbps Super G technology, which supports data rates at up to twice the standard 802.11g (according to Netgear) when used with Netgear wireless Ethernet adapters with Super G technology. The wireless Ethernet adapter used is Netgear's WG511T wireless 802.11g Ethernet adapter with Super G technology. While there will be similarities, other manufacturer's installation and setup will differ somewhat from what is shown here. However, the goals of these operations are the same. Different models of wireless equipment from the same manufacturer have also different installation programs and procedures. The user's guide for the devices you purchase should have the specific information you need. For the rest of this section, the term "WAP" will be used to describe both dedicated WAP devices and combination devices unless we need to distinguish between the two. Before we go into how to set the items, let's take a look at the items we will need to set.

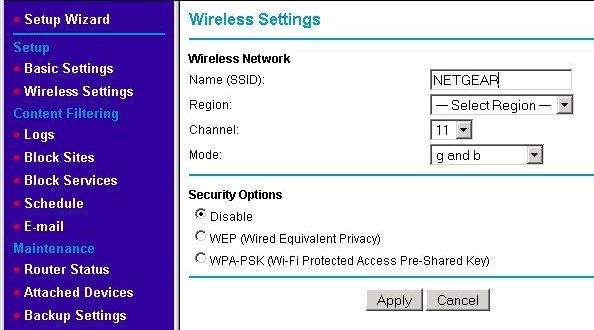

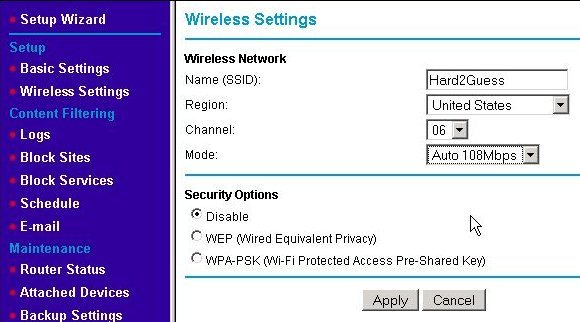

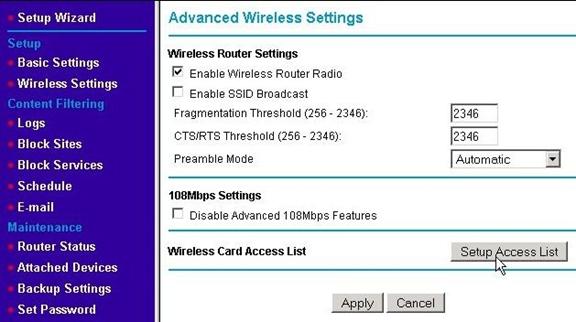

There are a large number of variables that can be set, but only a few of them must be set when establishing the radio connection. The first is to decide on the channel to be used. In 802.11b and g networks, the network transmits in the 2.4 GHz frequency band. However, there are multiple specific frequencies (channels) in that band that are available. The number and exact frequencies used vary depending on the country you live in. In the U.S., there are 11 channels numbered 1 through 11. This is one way that several discrete wireless LANs can be established in the same physical location. If you live in a dorm or townhouse environment and someone else purchases wireless equipment from the same manufacturer, the two radio transmissions will interfere with each other if they are both left at the defaults. If the default channel number for the WLAN is 6, you could decide to use channel 3 instead. That way, you can both have WLANs with overlapping operational ranges, but they won't interfere with each other. (If your neighbor has left his WLAN at the manufacturer's defaults and doesn't want to touch anything in case they "break it," you may have to get them to shut their WAP off until you get yours configured to not interfere.)

The second variable is the Server Set-Identification or SSID. This is the name of the WLAN assigned by the WAP. It is fairly arbitrary and you should feel free to give it a name you find easy to remember. Linksys WAPs like to use "linksys" or "wireless" as the default SSID. Netgear seems to use "NETGEAR." This isn't guaranteed by any means, and the manual that comes with the WAP will identify what the default channel and SSID is. (It is sometimes printed somewhere on the WAP itself as well.) Technically, two (or more) WLANs operating on the same channel, but using different SSIDs can also to co-exist, but the transceivers on all the WAPs and wireless Ethernet adapters will see all the WLAN traffic. They will ignore the traffic without the proper SSID. However, if the WAPs are operating on different frequencies, they will have less radio traffic to inspect, and the throughput will be higher. If you know you have a neighbor operating a wireless LAN, you should find out what channel they are using and pick a different one if possible. (One caveat: if you decide to use Netgear's proprietary Super G 108 Mbps speed, only channel 6 can be selected. Therefore, a different SSID would have to be use to differentiate two Netgear WAPs if both are using the Super G mode.)

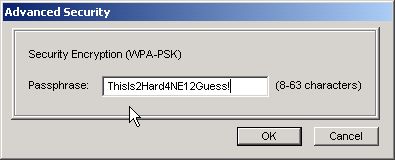

A third variable is the encryption settings, which we will leave for later. Using a secret key you choose for your network, all traffic will be encrypted at a level that will make it unreadable by others with a wireless Ethernet adapter if they happen to come in the transmission range of your WAP. Most WAPs come with the encryption disabled (although some come with it enabled and with a initial, random secret key printed on the WAP). While this aids in the initial setup of the WLAN (by removing one of the variables to contend with), it's not how you want to operate normally. We'll leave it disabled for now until we get the basic network up and going. In practice, you do not want to operate your WLAN without some form of encryption.

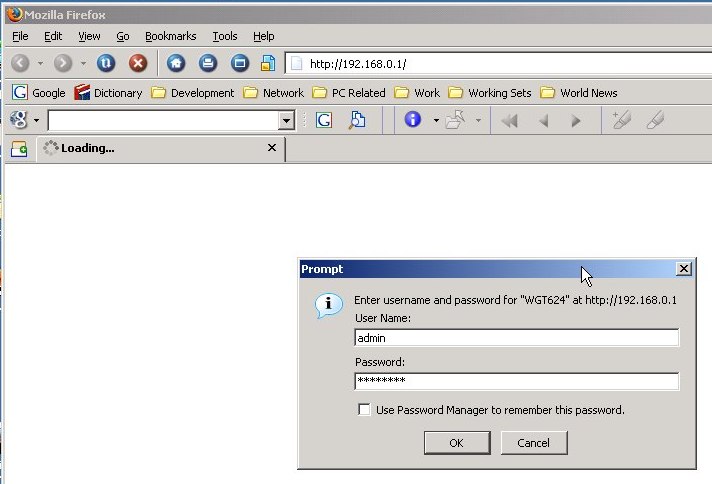

Most WAPs can be (or must be) configured using a web browser like Internet Explorer. The WAP has a built-in, specialized web server used for configuration. Rather than browsing to a well-known URL like www.google.com, you instead browse to the internal LAN address of the WAP. For the Linksys WRT54G and most other Linksys combination devices, that address is 192.168.1.1 by default, so http://192.168.1.1 is the address of the main configuration page. For the Linksys WAP54G, on the other hand, the default IP address is 192.168.1.245. The user's guide for your WAP will give the default IP address.

Here, we find ourselves in another chicken and egg situation. We would like to change the default settings of the WAP's channel and SSID. However, in order to do that with a wireless Ethernet adapter, we have to first talk to the WAP's configuration web pages using its default configuration. We will also need to configure the Ethernet adapter to have an IP address on the WAP's default LAN, which is a topic we really don't formally tackle until after the wireless radio medium configuration is completed. We have to do this in order to be able to contact the WAP, so that we can tell it what changes we want to make. (Note: If we are setting up a combination router/firewall/switch/WAP, this can also be done using a wired Ethernet adapter connected to one of the LAN ports on the switch portion of the box. However, this section will go over the general case that works for both standalone WAPs and combination router/WAPs.)

Set the Wireless Ethernet Adapter's Channel and SSID to the WAP's Defaults

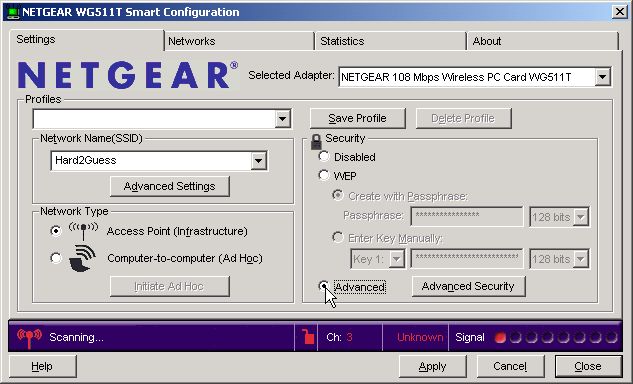

First, we need to set the default SSID in the wireless Ethernet adapter to match the default SSID of the WAP in order for the Ethernet adapter to be able to communicate with the WAP for the rest of the configuration. If you purchased your WAP and Ethernet adapter from the same manufacturer and they are complimentary models, the SSID of the adapter may already be set to match the WAP's SSID. If this is so, you can skip to the next section.

We change the SSID used by the wireless Ethernet adapter using the software supplied by the adapter's manufacturer. (Windows XP [at least since service pack 1 or 2] and Vista also come with the Wireless Network Setup Wizard. However, I've always had better luck with the manufacturer's programs written for their hardware.) With the wireless Ethernet adapter installed and powered up, we launch the configuration utility. Every wireless adapter I've had seems to come with a radically different looking configuration utility - even for different wireless models from the same manufacturer. For this example, I'm using a Netgear WG511T 802.11G wireless Ethernet adapter. I also have the Linksys WPC54GS wireless Ethernet adapter, which has a very different looking utility, but with more or less, the same functionality. If the utility for your wireless adapter doesn't look like the screens shown here, don't fret about it. Just try to understand the purpose of what's being done, and you should be able to translate it to your configuration utility. Our goal here is just to make sure that the adapter is using the same SSID as the WAP.

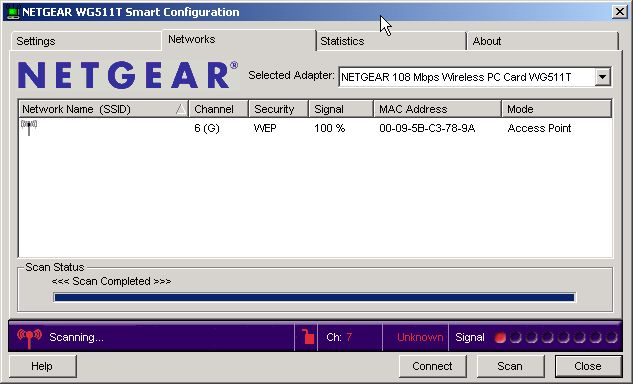

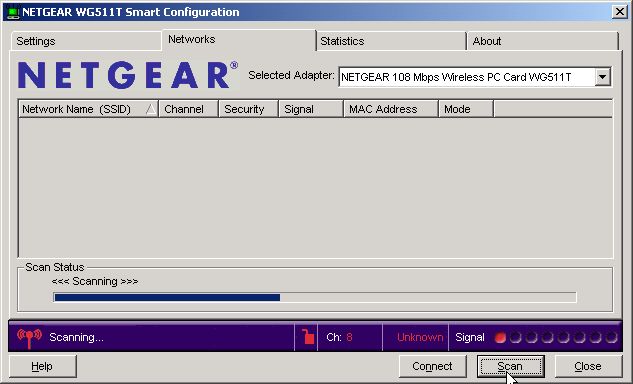

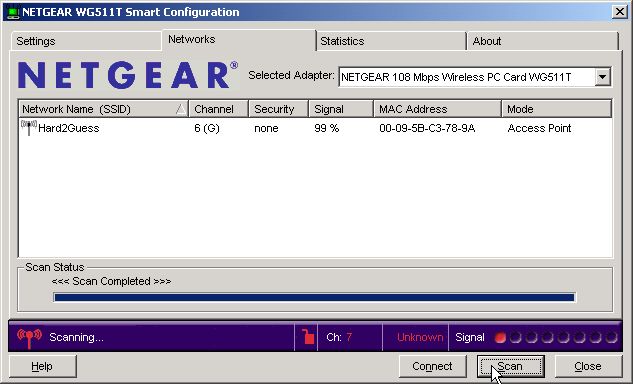

The Netgear wireless utility for its wireless adapter - NETGEAR WGS511T Smart Configuration - has the ability to scan for wireless networks that are within range. If we didn't know (or forgot) the default SSID of the wireless access point, we could use this utility to find out. (However, our home WAP can be set to not broadcast its SSID, so this may not work.) In order to do that with the Smart Configuration utility, we open it and pick the Networks tab. Clicking on the Scan button starts a scan.

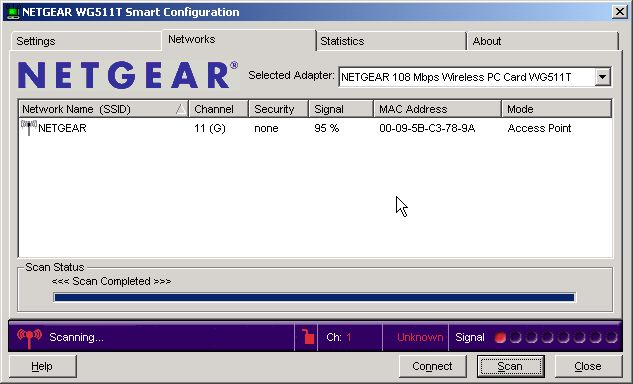

When the scan has completed, any networks found are displayed as shown below. This WAP is still set to its default values, namely an SSID of "NETGEAR" and no security. (The user's manual said the same thing, so this isn't much of a surprise.)

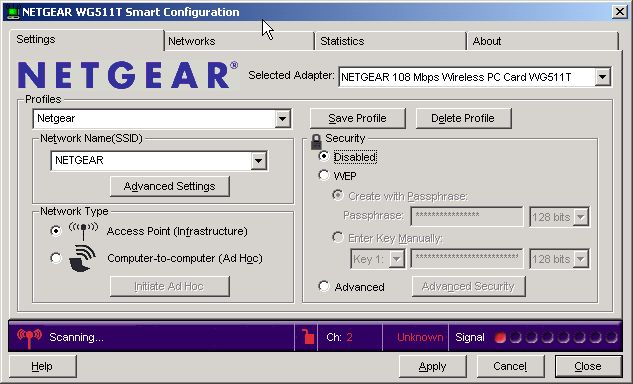

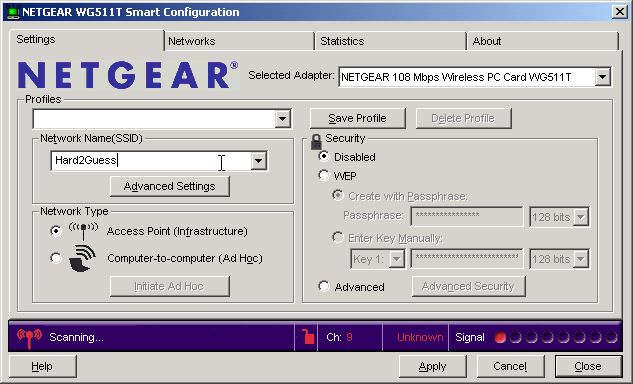

Now, we need to set our adapter to match the SSID of the WAP (if it's not already set to that value). The SSID setting for the WAP is the name of the network that it controls and needs to be the same for both the WAP and (all of) the wireless adapter(s). Once set for the Ethernet adapter, that SSID is the only network that it will pay attention to. If other wireless traffic from another SSID is broadcasting in the same area and on the same channel, both the WAP and wireless Ethernet adapters will ignore it. For the Netgear WGS511T, that SSID is changed on the Settings tab.

Above, I have set the name of the SSID to "NETGEAR" and I will save it in a profile named "Netgear." (Apparently, I wasn't feeling too inventive when I captured these screens.) Leave the security setting to "Disabled" (or change if to disabled if it isn't already) and hit the Apply button. (We will enable the security settings once we have established the basic wireless network. "Baby steps, Ellie, baby steps.") The result should be the screen picture below. That is, the Ethernet adapter should change from "Scanning" to displaying the new connection.

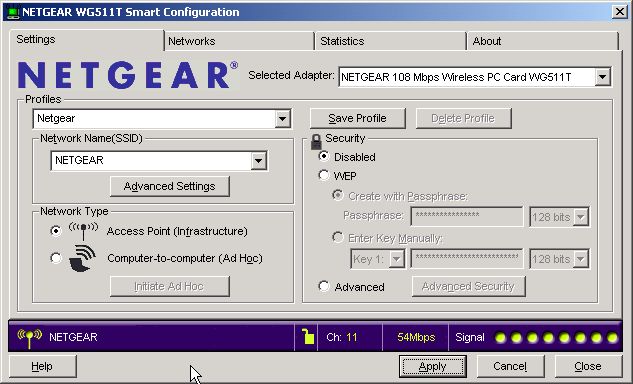

The status indicator line at the bottom of the screen now shows the wireless network we are connected to (NETGEAR), the channel being used (11), the current connection speed (54 Mbps at the moment, although this WAP and adapter card can go up to 108 Mbps), and the signal strength (8 of 8 dots or 100%; the WAP is just across the room from my laptop). I also clicked on the Save Profile button so I can recall this setup later if I need to. Using profiles comes in handy when we have a laptop that travels between wireless networks at home and work.

Note that we set the SSID, but we didn't set the channel. Most wireless Ethernet adapters will scan through the available channels and find the one your WAP is transmitting on. It will stop when it finds a WLAN that matches the SSID it is set to. If this does not happen, most cards will let you can set the channel manually. (This is left as an exercise for the reader.)

Now that the radio medium is established - the wireless equivalent of connecting the cable between the PC and the switch - we need to configure the Ethernet adapter to be on the same logical network as the WAP. That is, the adapter needs to have an IP address on the same network that the WAP operates its LAN and WLAN on. (However, it cannot be the exact IP address of the WAP; no two devices on the same network can share the same IP address.) Exactly what that IP address should be depends on the manufacturer (and possibly model) of your WAP. Assuming there is a router somewhere on your network - as will be the case if this is a combination router/switch/WAP - you may find that your newly-connected machine got a valid IP address using DHCP.

To make things simple and remove as many variables as possible, you may find it easier to set the address of the Ethernet adapter you are using (wired or wireless) manually to start with. It must be valid with respect to the WAP's default settings. For example, if the WAP uses 192.168.0.1 as its default LAN address, the manual setting for the adapter should be 192.168.0.xxx, where "xxx" can be any number between 2 and 254, inclusive. (You can't use 1 because the WAP has reserved that address for itself.) The manual that came with the WAP will tell you what the WAP's default LAN (a.k.a., inside, internal, local) IP address is by default. You will need to jump to section Fixed/Static IP (Manual) IP Assignment in order to find out how to set the IP address manually, and then return here.

Configuring the Wireless Router

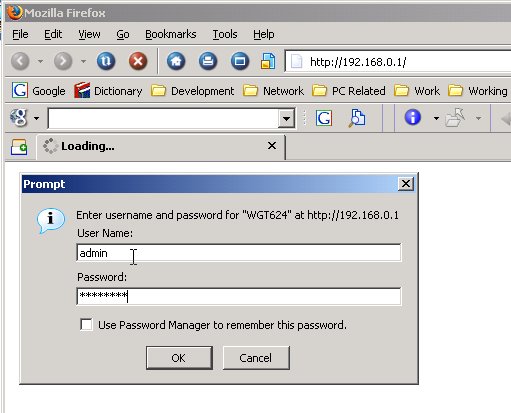

Configuring the Wireless RouterConnect to the Router/WAP's Configuration Pages

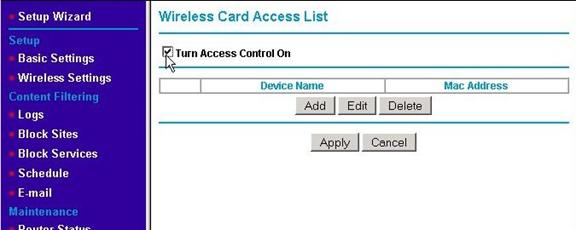

Now that your Ethernet adapter has the SSID of the WAP and an IP address on the WAP's network, we need to configure it to the settings we want for our wireless network. First, we just need to see if we can contact it at all. To test to see if we have our Ethernet adapter configured to talk with the WAP, let's bring up the WAP's administration pages. Most WAPs and Routers have a built-in mini web site that can be used to check their status and to change their configuration. So to view the WAP's settings, we use a web browser like Internet Explorer or Firefox just like we would use to visit any other web site. The user's guide that came with your WAP will tell you for sure, but typically you get to the WAP's configuration pages by browsing to 192.168.0.1 or 192.168.1.1 into the address bar. Linksys equipment, for example tends to use the "1.1" address. Netgear WAPs, typically use the ".0.1" address instead.